The Public Health Triumph No One's Talking About

Teens have stopped smoking — why aren't we celebrating?

Published in National Review on February 24, 2025.

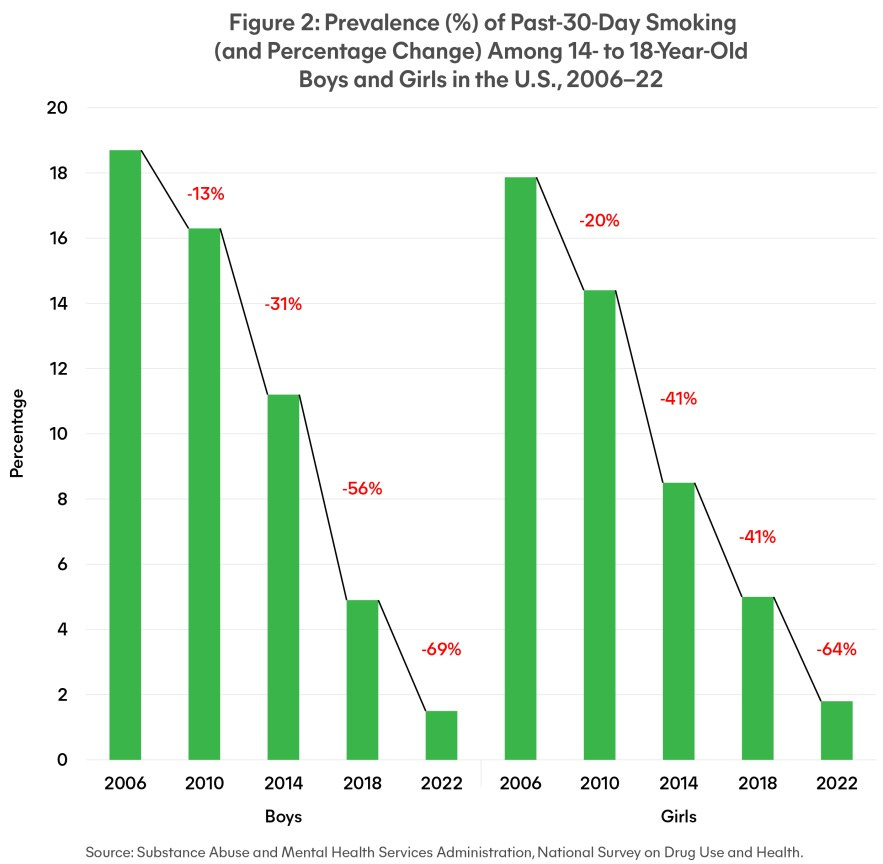

Teen smoking has virtually died out. This once unimaginable fact appears in the Centers for Disease Control’s report from the 2024 National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS). According to the survey, only 1.7 percent of high school students were current smokers (i.e., they had smoked on one day or more in the past month). In 2016, the rate was 8.3 percent, five-fold higher.

Champagne should be flowing. Yet no one, not the CDC, the Food and Drug Administration, the surgeon general, nor any member of the rest of the anti-smoking public health community, has issued a celebratory press release. Why?

Several reasons explain the silence — and they tell us a lot about the failure of anti-smoking agencies and entities to adapt to new information and adjust their priorities.

First, teens are vaping, a development incorrectly seen as scant improvement over smoking. “We are at risk of losing another generation to tobacco-caused diseases as the result of e-cigarettes,” warns the American Lung Association. This claim could not be more wrong, on several counts. Let’s examine the evidence.

Still, teens should not vape. That’s a given. The aerosol they inhale from an e-cigarette, a vape pen, or the popular Elf Bar may carry some harmful chemicals, and nicotine is an addictive substance. But for anyone who already smokes, switching to vaping is a responsible move if they’ve tried and failed to quit by using nicotine gum or a patch and cannot or will not give up nicotine.

This is because e-cigarettes are far less hazardous than cigarettes; they had been estimated by the Royal College of Physicians to be 95 percent less harmful. (The college now uses the phrase “substantially less harmful,” though it has not revised downward its numerical estimate.) The difference is that e-cigarettes do not combust tobacco (they don’t even contain tobacco), a process that releases tar, carbon monoxide, and dozens of carcinogens.

E-cigarette aerosol has fewer toxins than cigarette smoke, and those toxins the two do have in common are present at much lower levels in e-cigarettes.

This relative safety, however, has been downplayed, distorted, or denied by the American Lung Association, American Heart Association, the World Health Organization, and more.

The most salient question is what percentage of high schoolers use e-cigarettes in the absence of prior smoking or toking.

Data on such “virgin vapers,” a term coined by Brad Rodu, a professor of medicine at the University of Louisville, are available through the NYTS.

Rodu’s analysis of the latest (2023) NYTS public data release should allay some concerns (the CDC’s 2024 report gives only summary figures). For one, the overall population of current high school virgin vapers, while real, is a modest 235,000, or 1.5 percent of all 15.8 million high schoolers.

Fortunately, the majority of this group were not very frequent vapers. Almost two-thirds, or 63 percent, vaped only one to nine days in the past month, and another 6 percent vaped from ten to 19 days.

The most important, and worrisome, category — teens who vaped 20 to 30 days — was 31 percent, or 73,000. These frequent virgin vapers are at highest risk for being addicted to nicotine and vaping.

Fortunately, they represent only 0.46 percent (4.6 in 1,000) of all high school students in the U.S. Another way to look at it, Rodu says, “is that 88 percent of frequent teen vapers currently or ever used a tobacco or cannabis product.”

What do these figures mean for critics’ most high-profile warning about e-cigarettes — namely, that they are a meaningful gateway to smoking?

If anything, it is very likely that teens who once would have smoked cigarettes are vaping instead. In any event, it is clear that vaping in first-year high schoolers is not giving rise to a new cohort of smokers in the years following graduation, specifically from ages 18 to 20 (figure 3). Such a pattern is in keeping with another national survey’s finding that teens who vape say they were motivated to do so in order to avoid cigarettes, which they believe, correctly, are more harmful.

Does this mean that no 15-year-old ever moved on to smoking because he first vaped? “No,” says Clive Bates, former director of Action on Smoking and Health, a tobacco control group in the U.K., “but the aggregate effect at the population level appears to be negligible given the reduction in smoking initiation during the period of vaping’s ascendance.”

And yet the CDC, major tobacco control activists, health advocates, and some researchers continue to sound the alarm about a gateway effect.

Another exaggerated concern of vaping skeptics is the effect of nicotine on adolescent brains. Michael Bloomberg, a fierce detractor of e-cigarettes, warns without any clinical evidence that adolescent vapers risk IQ losses of up to 15 points “for the rest of [their] life.” The CDC states that “nicotine can harm brain development, which continues until about age 25.” Prominent anti-smoking organizations and the surgeon general also forecast bad outcomes.

In truth, there is little evidence that nicotine harms the developing teen brain. Although adolescent rats show neuronal alterations in the brain when they are injected with nicotine — a fact promoted as evidence of risk for human teens — what those changes mean is far from clear. (Never mentioned, notably, is the finding that nicotine — a drug in the same class as Adderall and a chemical with known neuroprotective properties — can actually enhance attention in rats.)

While teen smoking is linked with cognitive deficits during those developmental years, adolescents who smoke are far more likely to have preexisting conduct disorders, problems with impulse control, or mental illness. They are also more likely to have poor school performance or to entirely drop out of high school, but these are merely correlations.

In short, it is difficult to identify a causal link between adolescent smoking and brain function. Most likely a “common liability” explains the associations. This means that the same factors that incline young people to smoke also predispose them to engage in other risky behaviors or to develop mental conditions.

Finally, we can turn to the obvious fact that there are now about 29 million current and 56 million former smokers in the U.S. The overwhelming majority started in their youth and no neurodevelopmental deficits have been suspected or documented.

These widely held misconceptions about vaping that are endorsed and promulgated by the CDC, FDA, and surgeon general have kept them from acknowledging that a great public health stride has been made.

Their demonization of nicotine vaping is harmful. To begin with, it distracts from other risky behaviors that young people pursue, often in greater numbers. Consider: Of the 770,000 high school vapers who had never smoked a cigarette or cigar, 535,500 of them had also vaped marijuana-related products, according to Rodu’s analysis of the CDC data.

From 2018 to 2022, approximately 59,000 teens aged 15 to 19 years died in the U.S. Thirty-seven percent (21,600) of the deaths were from accidents, 20 percent (11,700) from homicide, and 19 percent (11,300) from intentional self-harm (suicide).

Compare these statistics with the number of adolescent deaths from vaping nicotine: zero.

“Because of these misplaced priorities, schools are using video surveillance to make sure no one is vaping in the bathroom, while letting kids use alcohol to their hearts’ content,” says Michael Siegel, professor of public health and community medicine at Tufts Medical School.

Fixating on teen vaping has also suppressed what should be a robust public health campaign to disseminate accurate information about vaping as a safer alternative for adult smokers who can’t or won’t quit.

Instead, misinformation is rampant. Warnings about dangerous levels of formaldehyde and toxic metals associated with vaping, as well as vaping-induced heart attacks and “popcorn” lung, have been flatly debunked. Yet the public has now imbibed these falsehoods.

Regarding nicotine, representative surveys found that between 80 and 90 percent of physicians strongly — and wrongly — agreed that nicotine directly contributes to the development of cardiovascular disease, chronic lung disease, and cancer. In truth, nicotine is a largely benign chemical.

The good news is that smoking among both adolescents and adults is the most uncommon it’s ever been. But hailing the success in slashing teen smoking, made partly possible by their migration to vaping, first requires acknowledging the truth about vaping.

In the end, the half million people who are dying each year from cigarettes, inveterate smokers for whom e-cigarettes were first made widely available about ten years ago, are being failed by those who once set out to save them.

As for America’s youth, the news is excellent, if unheralded. “The near disappearance of youth smoking is one of the greatest public health achievements of the present century,” Kenneth Warner, emeritus professor of public health at the University of Michigan, told me. “We should be shouting it from the mountaintops.”

Shared w multiple colleagues in the substance use treatment filed here in Boston and my grandkids and their friends

They’ve given it up for meth?